On the old Blanchisseuse Road, where the jungle presses close and the river bends sharply beneath overhanging trees, travelers once learned to fear the hour when the moon stood highest. At that bend, where stones glistened like bones beneath shallow water, a woman appeared each night to wash linen that never grew clean.

Long before she became a whisper on the road, the woman had been called Mercy. She was enslaved on a French Creole estate in the northern valleys of Trinidad, owned by a master who measured a household’s dignity by the whiteness of its cloth. Mercy was made to wash endlessly. From before dawn until after dark, she knelt at the river, beating sheets against the rocks with raw hands, scrubbing bloodstains from childbirth linens and sweat from plantation labor. Lye burned her skin. Cold water split her knuckles. Rest was never permitted.

When her body finally failed, she was buried without prayer near the same river that had consumed her strength. The road that later passed there carried her memory into the night.

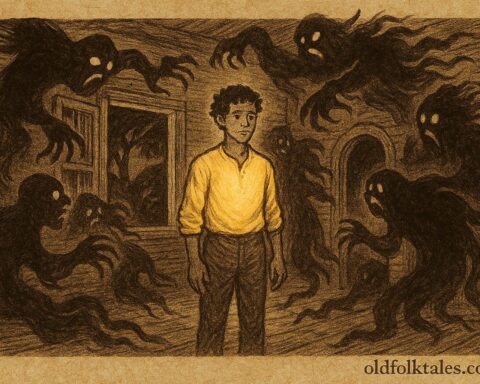

After her death, people began to see her.

At midnight, when the frogs fell silent and the forest held its breath, Mercy appeared at the riverbend. She was no beauty as other spirits were rumored to be. Her back was bent. Her arms hung long and swollen. Her clothes clung wetly to her body, and her face bore the deep exhaustion of a woman who had never been allowed to stop working.

She knelt in the river and washed.

The sound came first. A steady slap of cloth against stone. Travelers walking late would slow without knowing why, their feet turning toward the water. They would see her there, beating heavy linen on the rocks. The sheets were stained dark, and as she wrung them, the water ran rust-brown, then slowly red.

She never spoke first.

Those who passed were compelled to help. Their hands would reach for the cloth as if pulled by invisible threads. The linen was always heavy, always cold, always slick with water that refused to clear.

If the traveler helped her quietly, without complaint or mockery, Mercy would finally lift her head. Her eyes were deep and hollow, but not cruel. She would point to a place in the riverbed and vanish without sound.

At dawn, that traveler would return and find a small silver coin wedged between stones, or a trinket long lost and mourned. It was never great wealth, only enough to remind them that kindness had weight in the world.

But not all showed compassion.

Some cursed her. Some recoiled in disgust. Some laughed and refused.

To them, Mercy rose silently from the river, lifted a soaking sheet, and cast it over their heads. The cloth pressed heavy and cold, smelling of lye and iron. Those travelers were found the next morning drowned in inches of water, their bodies twisted as if wrung dry, the scent of soap clinging to their skin.

The washerwoman never chased. She never screamed. The punishment came as quietly as the labor she had endured.

Elders warned children never to mock working hands. They warned travelers never to pass a river at midnight without humility. And they said Mercy still washed because no one had ever washed the debt owed to her.

The river remembers her hands. The road remembers her name.

Moral Lesson

This folktale teaches that compassion toward suffering labor is sacred. Those who respect the weight of another’s pain are protected, while cruelty and indifference invite destruction. Mercy’s story preserves the memory of enslaved labor and warns that injustice leaves spirits behind.

Knowledge Check

1. Who is the Midnight Washerwoman?

She is the spirit of Mercy, an enslaved woman worked to death washing linen.

2. Where does the story take place?

Along Blanchisseuse Road near a river bend in Trinidad.

3. What compels travelers to help her?

A supernatural force tied to her unresolved suffering and labor.

4. What happens to kind travelers?

They are rewarded with a silver coin or lost object at dawn.

5. What happens to cruel travelers?

They are drowned by the washerwoman’s cursed linen.

6. What does the washerwoman symbolize?

The unacknowledged suffering of enslaved labor and moral consequence.

Source and Cultural Origin

Source: French Creole folktale, Trinidad

Collected by C.R. Ottley from the Arouca district

Cultural Origin: French Creole Caribbean folklore, linked to enslaved washerwomen and plantation history