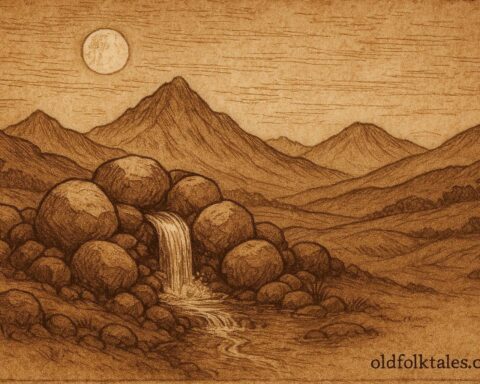

In the southern Andes of what is now Chile, where mist clung to the slopes and the earth folded into itself like an old memory, there stood a hill known as Wira Apun. To travelers, it looked ordinary. Its surface was uneven, its grasses thin, and its stones darkened by time. But to the people of the nearby valley, the hill was not merely land. It was a guardian.

The elders said Wira Apun was older than the village itself. Long before houses were raised or paths carved into the soil, the hill had been chosen as a resting place for the dead. Generations of ancestors lay beneath its surface, wrapped in earth and memory. No walls marked their graves. No monuments stood above them. The hill itself was the marker.

Burial at Wira Apun followed strict customs. The dead were carried at dawn, when the air was still and listening. No loud voices were allowed. No metal tools were used to cut the earth. Graves were shallow and returned gently to their original shape, so the hill would not feel wounded.

Discover the vibrant legends of Guatemala, Honduras, and Costa Rica in our folktale collection.

The living believed the ancestors remained aware. Not as spirits wandering freely, but as presence embedded in stone, soil, and slope. Wira Apun was said to breathe slowly, rising and settling with the seasons. When the wind changed direction suddenly near the hill, people said the dead were speaking among themselves.

For many years, no one challenged this understanding.

Then came the road builders.

Officials from the lowlands arrived with measuring tools and papers stamped with authority. They spoke of progress and connection. A new road, they said, would shorten travel between towns and bring trade and opportunity. The planned route cut directly across Wira Apun.

The villagers protested quietly. They explained the hill’s meaning. They spoke of burial grounds and ancestral law. The officials listened politely but dismissed the claims as superstition. There were no visible graves, no records recognized by the state. To them, the hill was unused land.

Work began at the start of the dry season.

The first sign came early. Survey markers placed along the slope vanished overnight. Workers blamed animals. The markers were replaced. Again, they disappeared.

Then the ground itself began to shift.

Not violently. Not like an earthquake. The change was subtle but undeniable. Paths carved one day no longer aligned the next. Stones rolled into new positions without sound. Shallow cuts in the soil softened and closed as if pressed from below.

The workers argued among themselves. Some refused to continue, saying the land felt unstable. Others accused the villagers of sabotage. Officials ordered the work to continue.

On the seventh morning, a trench collapsed without warning. No one was injured, but the shape of the hill had changed. A ridge that had not been there before now rose like a bent shoulder across the planned route.

Elder Amaru, the oldest man in the village, walked alone to the hill that evening. He placed his ear to the ground and remained there until the stars appeared. When he returned, his voice trembled—not with fear, but with certainty.

“The dead are not fleeing,” he said. “They are standing.”

The next days brought heavier resistance. Tools broke without reason. Ropes snapped. The hill’s surface hardened in some places and loosened in others. Maps no longer matched the terrain. What had been measured became unreliable.

At night, villagers reported hearing deep sounds, like distant breathing or slow movement beneath stone. No one panicked. Instead, families began leaving offerings again—water, woven cloth, quiet words of acknowledgment.

The officials, growing frustrated, brought in heavier equipment.

That was when the hill moved openly.

At midday, under clear skies, the slope folded inward on itself, creating a shallow basin where the main road was planned. Nearby ground rose slightly, redirecting runoff and making the area unworkable. The change happened slowly enough to be seen, but too steadily to be stopped.

No earth shook. No rock shattered. The hill simply rearranged itself.

Work was suspended.

Experts were called. They spoke of unstable layers and ancient geological faults. Yet none could explain why the movement followed burial patterns known only to the elders. Graves that should have been exposed remained untouched. The altered land curved protectively around ancestral resting places.

Eventually, the road was rerouted.

Officials never admitted defeat. They blamed technical challenges and cost. But the villagers knew the truth. Wira Apun had fulfilled its role.

In the seasons that followed, the hill returned to stillness. Not to its old shape, but to a new one that made disturbance difficult. Children were taught to observe it closely. “If it changes,” elders said, “it is because we have forgotten something.”

To this day, travelers passing nearby notice that paths bend strangely around the hill. Maps show inconsistencies. Locals simply nod and say, “The ancestors are still there.”

Click to read all South American Folktales — timeless stories from the Andes to the Amazon.

Moral Lesson

This story teaches that sacred spaces are not passive. When communities honor their dead and protect ancestral memory, the land itself becomes a guardian. Disrespect toward burial grounds is not merely cultural loss but a rupture that the earth will resist.

Knowledge Check

- Why was Wira Apun considered sacred?

Answer: It served as an ancestral burial hill for generations. - What triggered the hill’s movement?

Answer: Attempts to build a road through the burial site. - How did the hill protect the graves?

Answer: By shifting its shape to block construction and shield burial areas. - Who interpreted the hill’s actions correctly?

Answer: Elder Amaru. - What decision was eventually made about the road?

Answer: The road was rerouted away from the hill. - What does the hill symbolize in the story?

Answer: Living landscapes acting as guardians of sacred memory.

Source: Adapted from Ancestral Burial Landscapes of the Andes, Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino (2013)

Cultural Origin: Andean peoples, Chile