Dulcera is the name whispered by elders when dusk settles over the market roads of Sololá and the crossroads grow quiet. In the fading light, when vendors have packed away their baskets and only the smell of sugar and roasted seeds lingers in the air, she appears. She is an old woman, small and bent, standing alone where paths intersect, holding a brilliantly painted cántaro pressed against her hip.

Her clay pot gleams with colors too bright for evening. Reds glow like embers. Yellows shimmer as though lit from within. From it, she offers sweets no child can resist. Alborotos crackle softly. Pepitorias shine with syrup. Canillitas de leche look impossibly smooth and white. They glisten unnaturally, as if the last light of day has chosen them as its resting place.

Children are drawn to her without knowing why. She does not shout or beckon. She only smiles, her face lined deeply, her eyes patient. Coins exchanged, the candies melt on the tongue, sweeter than anything bought during daylight. The old woman nods once, and then she is gone, leaving only the empty crossroads and a faint scent of sugar.

That night, the child grows warm. A fever settles in, heavy and sudden. Sleep comes quickly and deeply, carrying the child into a dream unlike any other. In the dream, the world is made of sweetness. The ground clings like syrup. Hills rise in soft, sticky folds. The air tastes of sugar, and every step is harder than the last.

From the distance comes a sound. Scrape. Scrape. Scrape.

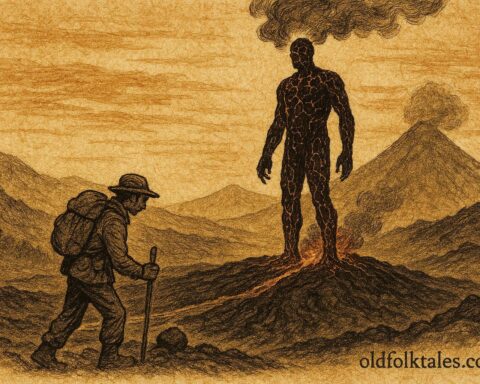

The Dulcera appears, no longer small. She towers above the landscape, holding a giant spoon that glints like polished bone. She chases the child through the cloying world, her laughter echoing, not cruel but relentless. No matter how fast the child runs, the sweetness pulls them back, weighing their body down until they cannot move.

When morning comes, the child does not wake.

Parents recognize the signs immediately. This is empacho, the folk illness caused when food becomes lodged and refuses to move, trapping the body between hunger and excess. They know this sickness does not come from chance. It comes from the crossroads.

A curandera is called. She arrives quietly, carrying oils and herbs, her presence calm and steady. She lays the child down and begins the sobada, the ritual massage passed down through generations. Her hands press and pull with practiced care, following pathways older than memory.

As she works, she recites the counterspell, naming the seven crossroads of the town, one by one. Each name anchors the child back to the waking world, pulling them away from the sticky dream. The words are firm, respectful. The Dulcera is not insulted. She is acknowledged.

At the end of the ritual, the child retches and vomits a strange substance, thick and sweet, tasting faintly of candy. The fever breaks. The dream dissolves. By morning, the child wakes weak but alive, with no memory of the spoon or the chase.

The elders say the Dulcera is not evil. She is a teaching spirit, born from hunger and indulgence, from children left unwatched and food eaten without blessing. She punishes greed gently but firmly, reminding families that sweetness must be respected, not devoured without care.

Even now, when dusk falls near the markets, parents call their children home early. They watch the crossroads carefully. And when a clay pot flashes with impossible color in the dying light, they turn away, knowing the lesson has already been taught.

Moral Lesson

Desire without restraint brings harm. The Dulcera teaches that care, moderation, and respect for food protect both body and spirit.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is the Dulcera in Kaqchikel folklore?

A1: A spirit associated with temptation, sweets, and the illness known as empacho.

Q2: Where does the Dulcera appear?

A2: At deserted crossroads near markets at dusk.

Q3: What happens to children who eat her candies?

A3: They fall into a fevered sleep and experience a sticky, frightening dream.

Q4: How is the illness cured?

A4: Through a curandera’s sobada ritual and a spoken counterspell.

Q5: What does the giant spoon symbolize?

A5: Excess and the burden of unchecked indulgence.

Q6: Is the Dulcera considered evil?

A6: No, she is a teaching spirit who corrects greed and neglect.

Cultural Origin and Source

Source: Maya Kaqchikel folktale, Guatemala

Documented in oral tradition projects by Universidad Rafael Landívar, Sololá region.