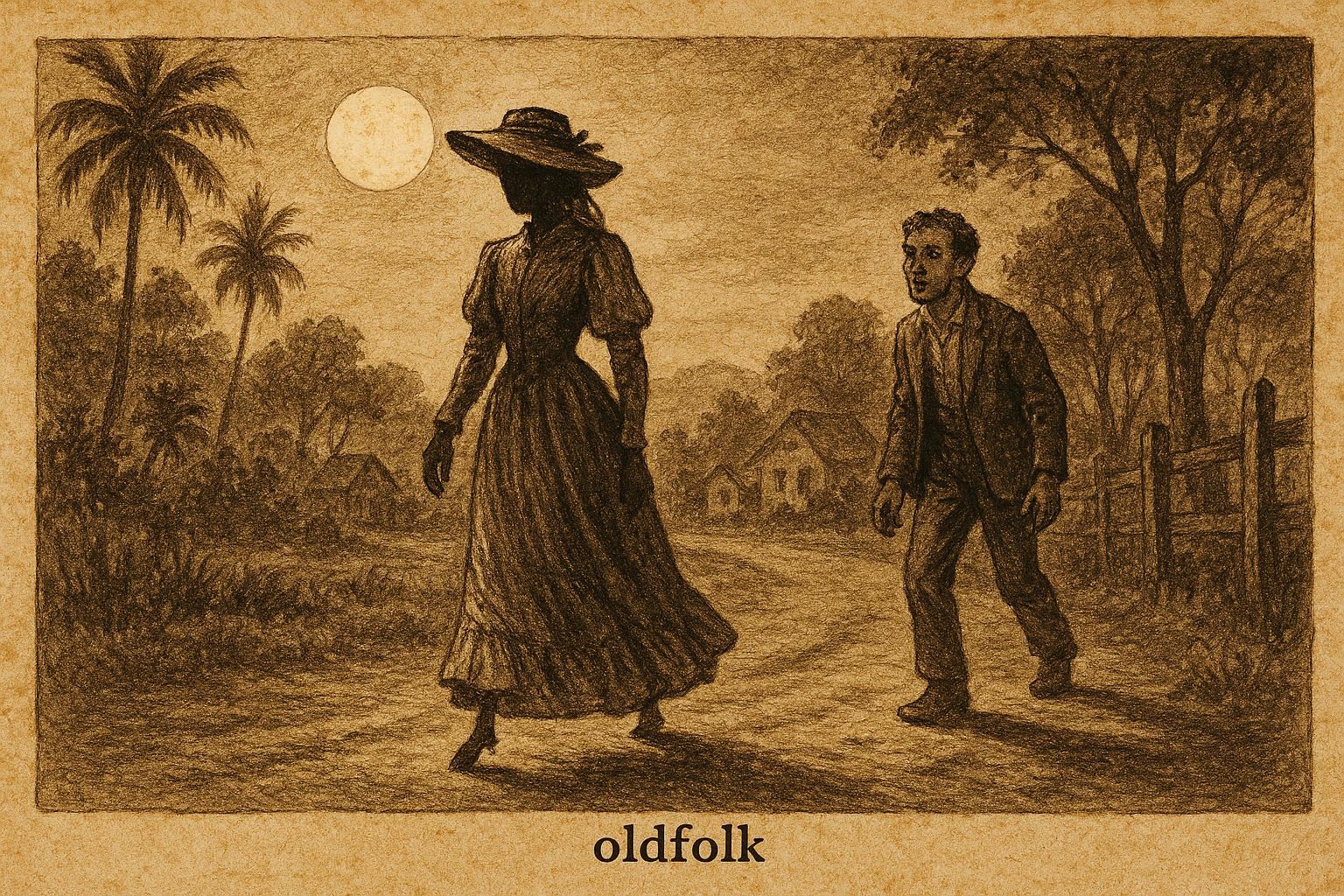

On the nights of a full moon in Trinidad, when the scent of night-blooming jasmine hangs heavy in the air, the wise villagers keep close to home and to company. For it is on such nights that La Diablesse walks. She is not a creature of the forest or the grave, but a spirit of temptation itself, born from the old, blended stories of the island, a she-devil of Afro-Creole lore with a French-Creole name and a planter’s lady’s grace.

You would not know her for a devil at first glance. Far from it. She appears as a vision of breathtaking, aristocratic beauty. She is tall and carries herself with a regal poise that makes other women seem like clumsy girls. She wears the fine, old-fashioned dress of a bygone era, a long, elegant douillette of rich fabric, embroidered with delicate patterns that catch the moonlight. Upon her head rests a wide-brimmed hat, a tantana, often adorned with lace or a feather, casting a deep shadow that mysteriously obscures her face, yet hints at its perfection. Sometimes a thin veil adds to her allure. She smells of expensive perfume and the faint, intoxicating powder of another century.

You will find her where men are vulnerable: at the edges of a bustling village fete, or gliding silently down a lonely moonlit road that cuts between the cane fields and the dark wall of the jungle. She does not speak loudly. Her power is in her presence, a magnetic pull. Her target is always a man—specifically one who is already straying: the husband with a wandering eye, the drunkard leaving the rum shop, the young braggart full of false courage.

She will catch his gaze from beneath her hat-brim and offer the ghost of a smile. Then, she will turn and begin to walk slowly away, the sound of her petticoat whispering a rhythmic chac-chac, chac-chac like a seductive promise. It is a sound meant to pull a man from his senses, to make him forget his home, his wife, his very name. He will follow, drawn by her beauty and the promise of a forbidden romance.

For a time, the walk is pleasant. She leads him off the main road, onto a faint, winding track. The sounds of the village fade, replaced by the chorus of frogs and the rustle of unseen things in the bush. The moon, his only lantern, paints the world in silver and deep shadow. This is when the vigilant man might be saved. For as La Diablesse walks, the moonlight may fall just so, illuminating the hem of her lavish dress as she steps over a root or a stone. A sharp eye will see that from beneath the fine embroidery, there does not emerge a delicate slipper, but the hard, unmistakable cleft of a cloven hoof, the foot of a goat, of the devil himself.

If he sees it, and his blood turns to ice, he must do one thing: turn away immediately. He must cross himself, if he is a believer, or throw salt over his shoulder. He must run without looking back, for the spell is broken only by recognition and retreat.

But if he is too mesmerized, too foolish, or too deep in his cups to notice, the walk continues. La Diablesse leads him deeper, the path growing steeper and more treacherous. She leads him through thorny thickets that tear his clothes, across streams that chill his bones, and finally to the edge of a sheer ravine or a deep, wild precipice. Her chac-chac grows fainter. Then, at the very moment he expects her embrace, she simply vanishes. One second she is there, a silhouette against the moon; the next, there is only empty night.

The man is left utterly alone, miles from anywhere he knows, lost in the heart of the wilderness. He may fall from the ravine in his shock. He may be set upon by animals, or wander for days in a confused panic, scratched, bitten, and half-mad with fear. He is not physically attacked by her; he is delivered to his own punishment. La Diablesse is the spirit of retribution. She punishes the unfaithful, the arrogant, the morally weak. She is the consequence that finds you when you choose to follow a beautiful lie off the safe path.

He may eventually stumble back to his village, days later, a broken man with a wild story no one fully believes. But the old ones, nodding knowingly, will understand. They will whisper, “He met La Diablesse. She showed him her hoof, but he was too blind to see.”

The Moral Lesson:

The legend of La Diablesse is a powerful warning against the perils of temptation, superficial beauty, and moral weakness. It teaches that not everything beautiful is good, that deception often wears a lovely face, and that straying from the right path, literally and morally, can lead to being lost, harmed, or ruined by the consequences of one’s own poor choices.

Knowledge Check

Q1: How does La Diablesse appear to her victims?

A1: She appears as an impossibly elegant, tall, and beautiful woman wearing an old-fashioned, embroidered long dress (douillette), a wide-brimmed hat (tantana), and sometimes a veil, exuding an aura of aristocratic charm.

Q2: What is the tell-tale sign that reveals her true, devilish nature?

A2: Beneath the hem of her lavish dress, one of her feet is not human but a cloven hoof, like that of a goat or devil, often revealed by moonlight as she walks.

Q3: What auditory lure does La Diablesse use to attract men?

A3: The rhythmic, seductive rustle of her petticoat, known as the chac-chac, which acts as a hypnotic sound to draw men away from safety.

Q4: What is La Diablesse’s ultimate goal with the men she lures?

A4: She does not physically attack them. She leads them deep into the wilderness to the edge of a ravine or dangerous place, then vanishes, leaving them lost, injured, or at the mercy of the elements as punishment for their moral failings.

Q5: What type of man is most often targeted by La Diablesse?

A5: She targets men exhibiting moral transgression or foolishness, the unfaithful husband, the drunken braggart, or the easily tempted, who choose to follow her away from the safety of community.

Q6: What cultural roots and era does the figure of La Diablesse reflect?

A6: She is a figure from Afro-Trinidadian Creole folklore, blended with French-Creole aesthetics (name, clothing), reflecting the social layers and tensions of the island’s plantation era.

Cultural Origin: Trinidadian Folklore (Afro-Trinidadian Creole).

Source: Common narrative from collections like those of C.R. Ottley and J.D. Elder, detailed in cultural repositories such as NALIS and the Caribbean Folklore Project.