Fuego is not only the flame that glows within Volcán Pacaya but the living presence believed to guard it. In the villages surrounding the volcano, elders say Pacaya is not empty stone or restless earth. It is a dwelling place. It belongs to El Viejo de Fuego, the Old Man of Fire, whose vigilance has shaped both the land and the conduct of those who walk upon it.

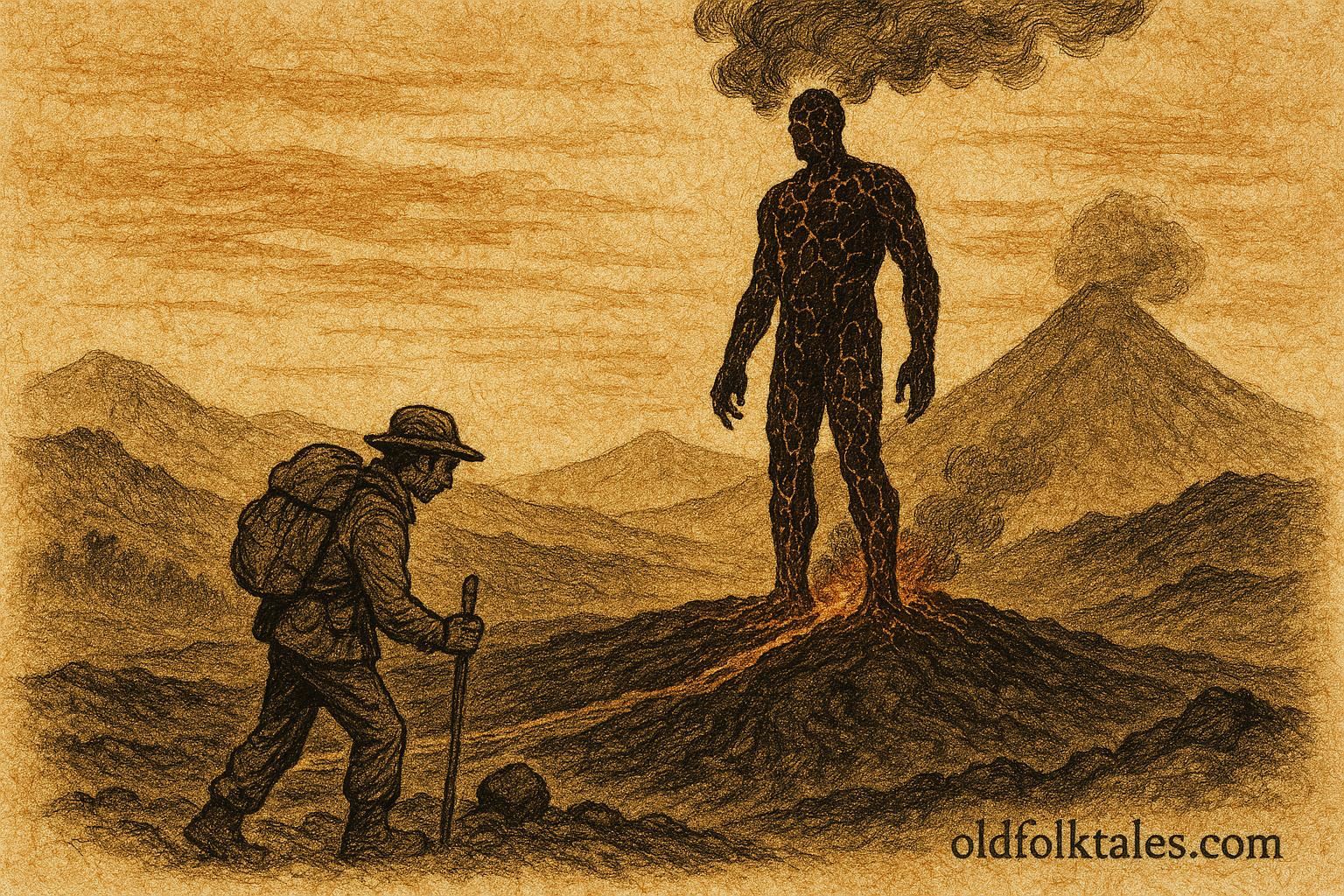

El Viejo de Fuego is described as towering and broad, his skin cracked like cooled lava, dark and veined with faint embers. Smoke rises where hair should be, curling slowly into the sky. He walks the campos de lava with deliberate steps, his weight pressing ancient authority into the ground. He is not quick to anger, but he is exacting. The mountain, he insists, must remain whole.

Travelers and hikers are drawn to Pacaya’s slopes by curiosity and wonder. The lava fields appear frozen in motion, sharp and black, streaked with red where heat still breathes beneath the surface. Some visitors, unable to resist, stoop to pick up lava rocks as souvenirs. They slip them into pockets or backpacks, believing stone can be taken without consequence.

That night, the mountain answers.

The stolen rock begins to burn, though it shows no flame. Heat spreads through cloth and skin, growing unbearable. Sleep becomes impossible. Then comes the voice, rough and gravelly, as though dragged through ash: “Lo que es de la montaña, a la montaña regresa.” What belongs to the mountain must return.

Those who ignore the warning suffer further. A dry cough settles in their chest, deep and persistent, as if their lungs have filled with volcanic dust. The villagers call it “the volcano’s breath.” No medicine quiets it. No rest relieves it. Only acknowledgment brings relief.

Some travelers hurry back, returning the rock to the slope where it was taken, setting it gently upon the lava fields. Others, already far away, send the stone back by mail, wrapped carefully, humbled by fear and awe. In more serious cases, a local shaman must intervene. The rock is replanted on the mountain with care, accompanied by an offering of aguardiente poured onto the ground, a gesture of respect to El Viejo de Fuego.

Only then does the cough fade. Only then does the heat leave the body.

The elders explain that El Viejo de Fuego is not cruel. He is a guardian, a steward of balance. Long ago, they say, he was a hermit saint who lived near the volcano, tending the land and warning others to treat it with reverence. Over time, his spirit fused with the fire itself, becoming something older and more elemental. He does not demand worship, only obedience to the natural order.

Even now, villagers teach their children never to take from Pacaya without permission, and never to mistake silence for absence. The mountain sees. The fire remembers. And El Viejo de Fuego walks still, ensuring that what belongs to the mountain always finds its way home.

Moral Lesson

Respect for nature is not optional. El Viejo de Fuego teaches that taking without permission disrupts balance, and that the land demands accountability.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is El Viejo de Fuego?

A1: A volcanic guardian spirit believed to inhabit Volcán Pacaya.

Q2: What action provokes his punishment?

A2: Taking lava rocks from the volcano as souvenirs.

Q3: What is “the volcano’s breath”?

A3: A persistent dry cough caused by offending the mountain.

Q4: How can the curse be lifted?

A4: By returning the rock directly or through ritual replanting.

Q5: What offering is made during the ritual?

A5: Aguardiente poured onto the volcanic ground.

Q6: What does El Viejo de Fuego represent culturally?

A6: Ecological balance and respect for sacred land.

Cultural Origin and Source

Source: Ladino folktale, Guatemala

Collected in San Vicente Pacaya by folklorist Celso Narciso Taxá.