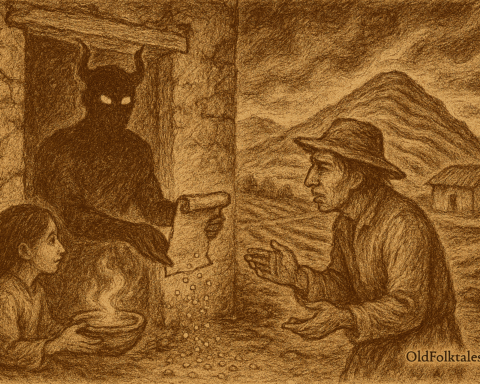

In the ancient times, when the boundaries between the sacred and the profane were still being established, when the great huacas still spoke directly to their people and the rules of proper living were being written into the fabric of the world, there lived two men in neighboring villages high in the Peruvian Andes. These men were brothers-in-law, bound by marriage but divided by character, and their stories would forever explain why some things are sacred in their proper time but destructive when removed from ritual context.

The first man was named Chaqui, which means “foot” or “foundation,” for he was meant to be solid and grounded. But Chaqui had developed a dangerous fondness for chicha, the sacred corn beer that flowed freely during festivals and ceremonies. He loved the warmth it brought to his belly, the way it loosened his tongue and lightened his burdens, the temporary escape it offered from the hard realities of mountain life.

Click to read all South American Folktales — timeless stories from the Andes to the Amazon.

Chicha was not forbidden far from it. It was a sacred drink, central to Quechua religious life. During festivals honoring the huacas and the apus, during planting and harvest ceremonies, during ritual gatherings that marked the turning of seasons and the celebration of community, chicha flowed like rivers. To drink during these times was not merely permitted but required, a way of participating in the divine order, of sharing in the collective joy and spiritual connection that bound the community together.

But Chaqui could not confine his drinking to these sacred occasions. He would drink in the morning when he should have been tending his fields. He would drink in the evening when his family needed him. He would drink alone, without ceremony or purpose, treating the sacred beverage as if it were ordinary refreshment rather than a ritual substance meant to connect humans with the divine realm.

His wife pleaded with him. “The chicha is for festivals,” she said. “It is for ceremonies, for times when the community gathers to honor the huacas. You dishonor it and yourself by drinking this way.”

But Chaqui would wave her concerns away with an unsteady hand. “Chicha is chicha,” he would reply. “Why should it matter when I drink it? The gods do not care about such small details.”

His brother-in-law, Haylli whose name means “triumph” or “celebration” was different in every way. Haylli also loved chicha, but he understood its sacred nature. He looked forward to festivals with genuine joy, not because he craved intoxication but because he valued the communal and spiritual experience that ritual drinking represented. During ceremonies, he drank deeply and celebrated fully, dancing and singing, joining his voice with others in praise of the divine powers. But when the festival ended and ordinary time resumed, he put away the chicha and returned to his daily work without complaint or longing.

The contrast between the two men grew more pronounced with each passing season. Chaqui’s fields became weedy and neglected. His llamas grew thin from insufficient care. His family suffered from his inattention and the resources he wasted on his constant, inappropriate drinking. Meanwhile, Haylli’s household prospered, his crops thrived, and his family lived in harmony and comfort.

The village elders spoke to Chaqui many times, warning him that he was violating sacred boundaries. “You treat chicha as if it were common water,” they told him. “You drink outside the proper ritual time and context. This is dangerous. You are confusing the sacred and the profane, mixing what should be kept separate. The huacas will not ignore this forever.”

But Chaqui, his judgment clouded by constant drinking, could not hear their wisdom. He continued his ways, growing more dissolute with each passing moon.

Then came the great festival of Inti Raymi, the celebration of the sun, one of the most important ceremonies in the Quechua calendar. The entire region gathered at the sacred site, bringing offerings of food, textiles, and vessels of chicha brewed specifically for this occasion. The ceremony lasted for days, filled with music, dance, prayers, and ritual consumption of the sacred drink.

Haylli participated fully and properly. He drank when the ceremonies called for drinking, he danced when the rituals required dancing, he joined in the communal prayers and offerings. He became intoxicated, as was appropriate during this sacred time, but his drunkenness was contained within the ritual structure, bounded by ceremony and purpose.

Chaqui also attended, but he arrived already drunk, having consumed chicha that morning outside any ritual context. During the ceremonies, he drank with no reverence or awareness of the sacred nature of what he was doing. He stumbled through the rituals, disrupted the prayers, and treated the holy occasion as merely another opportunity for personal indulgence.

As the final ceremony reached its climax, with the entire community gathered before the sacred altar, something extraordinary and terrible occurred. The sky darkened suddenly, though it was midday. A wind arose that seemed to come from nowhere and everywhere at once, carrying within it a presence that everyone recognized immediately the attention of the divine powers themselves.

Two columns of light descended from the roiling sky, one striking Haylli where he stood in proper ritual drunkenness, the other striking Chaqui where he swayed in his inappropriate intoxication.

The light that touched Haylli was golden and warm. It surrounded him like an embrace, and when it faded, he stood transformed. His eyes shone with inner light, and a blessing mark appeared on his forehead a sign that he had been touched by the divine and approved. From that day forward, Haylli would be known as a model of proper ritual conduct, and his family would be blessed with abundance and good fortune for generations.

The light that struck Chaqui was cold and white, harsh as lightning. He screamed once, a sound of terror and realization that came far too late. The light did not embrace him but consumed him, breaking him down into his constituent elements. When it faded, Chaqui was gone not dead in the ordinary sense, but unmade, destroyed for his violation of sacred boundaries. Where he had stood, there remained only a small pile of dust that the sacred wind scattered across the mountains.

The people who witnessed this were struck silent with awe and fear. They understood immediately what they had seen: a divine demonstration of the difference between sacred and profane use of ritual substances, between drinking within proper ceremonial context and drinking outside it.

The high priest spoke to the assembled crowd, his voice carrying the weight of revelation: “Let this be a lesson written into the very fabric of our world. Chicha is sacred when drunk in ritual time, during ceremonies and festivals that honor the divine powers. In these contexts, even drunkenness is holy, for it connects us to the spirit realm and binds our community together in shared celebration. But chicha drunk outside these times, consumed for personal pleasure or escape, becomes poison to the soul. It dishonors the gods, disrupts the sacred order, and will bring destruction upon those who cannot respect these boundaries.”

From that day forward, the story of Chaqui and Haylli was told and retold throughout the Andes. Parents taught it to their children, elders shared it with the young, and it became part of the fundamental education in what was sacred and what was profane, what was permitted and what was forbidden, and why context and intention matter as much as action itself.

The Quechua people continued to brew chicha and drink it joyfully during their festivals and ceremonies. But they never forgot Chaqui’s fate, the man who could not understand that the same substance could be both blessing and curse depending on when and how it was consumed. And they honored Haylli’s example, the man who showed that participating fully in ritual intoxication during proper ceremonies was not weakness but wisdom, not excess but sacred obligation.

Click to read all Andean Highland Folktales — echoing from the mountain peaks of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.

The Moral Lesson

This profound Huarochirí legend teaches the crucial Andean concept of sacred context and proper boundaries between ritual and daily life. The story demonstrates that actions, substances, and behaviors are not inherently good or bad, but become sacred or profane depending on their context, timing, and intention. Chaqui’s destruction and Haylli’s blessing illustrate that the same chicha that connects humans to the divine during ceremonies becomes destructive when consumed outside ritual boundaries. The tale emphasizes that ritual intoxication during festivals is not merely permitted but sacred and necessary for community cohesion and spiritual connection, while the same drinking in ordinary time violates cosmic order.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who were Chaqui and Haylli in this Quechua legend from Peru? Chaqui and Haylli were brothers-in-law in neighboring Andean villages who represented opposite approaches to ritual drinking. Chaqui drank chicha constantly outside ceremonial contexts, treating the sacred beverage as common refreshment. Haylli drank chicha only during proper festivals and ceremonies, participating fully in ritual intoxication while respecting sacred boundaries. Their contrasting fates established the rules for sacred versus profane use of ritual substances.

Q2: What is chicha and why is it sacred in Quechua culture? Chicha is a fermented corn beer that plays a central role in Quechua religious ceremonies and community festivals. It is considered a sacred substance used to connect humans with divine powers, honor the huacas and apus, and bind communities together during ritual celebrations. Drinking chicha during proper ceremonies is not just permitted but required as part of participating in the spiritual and social fabric of Andean life.

Q3: What was Chaqui’s transgression in this Andean tale? Chaqui’s transgression was drinking chicha outside its proper ritual context consuming the sacred beverage during ordinary time for personal pleasure rather than during ceremonies and festivals for spiritual and communal purposes. He violated the sacred boundary between ritual and daily life, treating what was holy as if it were common, thereby dishonoring both the drink and the divine powers it was meant to honor.

Q4: What happened to Chaqui and Haylli during the Inti Raymi ceremony? During the climax of the Inti Raymi sun festival, divine powers sent two columns of light from the sky. The golden light that struck Haylli blessed him for his proper ritual conduct, marking him with divine approval and ensuring prosperity for his lineage. The harsh white light that struck Chaqui destroyed him completely for his violation of sacred boundaries, reducing him to dust that scattered in the wind.

Q5: Why is ritual intoxication permitted during Quechua festivals but forbidden in daily life? According to this legend, intoxication during proper ceremonies is sacred because it occurs within ritual boundaries that connect participants to the divine realm and strengthen community bonds. The same substance becomes destructive outside ceremony because it violates the sacred order, treating holy things as common and disrupting the proper separation between ritual time and ordinary time. Context and intention transform the same action from sacred obligation to cosmic transgression.

Q6: What does this legend teach about sacred boundaries in Andean culture? The legend teaches the fundamental Andean principle that the universe operates through proper boundaries and distinctions between sacred and profane, ritual and ordinary, communal and individual. It demonstrates that substances, actions, and behaviors are not inherently good or evil but become one or the other depending on their context. Respecting these boundaries maintains cosmic order and brings blessing, while violating them brings chaos and destruction.

Source: Adapted from the Huarochirí Manuscript (Chapter 16) and Quechua ritual ethics texts

Cultural Origin: Quechua Indigenous Peoples, Huarochirí Province, Central Peruvian Andes