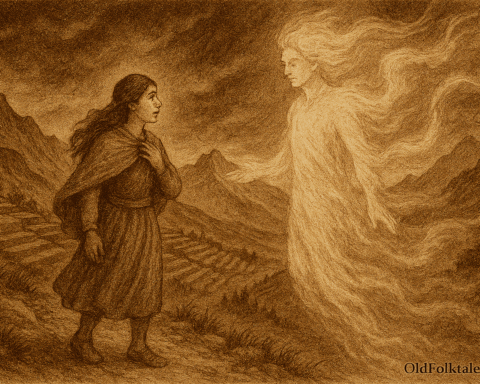

In the ancient days, when the apus, the sacred mountain spirits still walked openly among the people, there lived a woman named Kusisita in a small village nestled high in the Peruvian Andes. Her name meant “joyful,” and she had earned it well, for she was known throughout the community for her bright laughter and her refusal to let sorrow dim her spirit. She moved through life with a lightness that others admired, dancing at festivals and singing as she worked her fields.

Kusisita had married young to a man from a neighboring village, and though their union had been arranged, they had grown to care for each other. They lived a simple life, tending their terraced fields of quinoa and potatoes, raising their llamas, and participating in the endless cycle of planting and harvest that governed existence in the high mountains.

Click to read all South American Folktales — timeless stories from the Andes to the Amazon.

But one harsh winter, when the winds howled down from the snow-capped peaks and frost claimed the tender shoots in the fields, Kusisita’s husband fell ill. Despite the ministrations of the village healer, who burned sacred herbs and called upon the apus for intervention, the sickness consumed him. Within a moon’s passing, he was gone, leaving Kusisita a widow.

The entire community gathered for the funeral rites, as was proper and necessary. In the Quechua way, death was not a private affair but a communal event that required careful observance of ancient rituals. The mourning period was sacred, a time when the living honored the dead and helped guide the departed soul on its journey to the afterlife. Every member of the community had a role to play, and every ritual had its purpose in maintaining the delicate balance between the world of the living and the realm of the spirits.

The women of the village came to Kusisita, bringing her the rough black cloth she was expected to wear. They instructed her in the proper observances: she must wear only black for one full year, she must not sing or dance, she must not adorn herself with jewelry or bright colors, and she must participate in the monthly offerings at her husband’s burial site. She must weep publicly, demonstrating her grief to the community and the spirits alike. These rituals were not mere customs they were sacred obligations that connected the living to the dead and maintained harmony between the human world and the spirit realm.

But Kusisita looked at the black cloth and felt something harden in her heart.

“I will not wear black,” she announced to the astonished women. “I will not spend a year in darkness and sorrow. My husband is gone, and I cannot bring him back by wrapping myself in grief. Life is for the living, and I choose to live.”

The villagers were shocked by her words. The elders came to speak with her, explaining gently but firmly that the mourning rituals were not optional. They were the threads that held the community together, the sacred agreements between the people and the spirits who watched over them. To refuse mourning was to dishonor the dead, to disrespect the ancestors, and to invite the anger of the apus themselves.

But Kusisita would not be moved. She continued to wear her bright woven clothing, decorated with crimson and gold. She sang as she walked to her fields. When the community gathered for the monthly remembrance ceremonies, she refused to attend. When other widows wept and wailed in their grief, she remained silent and dry-eyed, her face set with stubborn defiance.

“I grieve in my own way,” she insisted. “My heart knows its own sorrow. I need no rituals to tell me how to feel.”

The villagers began to avoid her. What had once seemed like admirable strength now appeared as dangerous arrogance. She was breaking the sacred compact, disrupting the order that protected them all. But still, Kusisita persisted in her refusal, convinced that her personal truth was more important than communal obligation.

Then the spirits began to take notice.

At first, the signs were subtle. Kusisita’s fields, once lush and productive, began to wither. While her neighbors’ crops thrived, hers struggled and died, no matter how carefully she tended them. Her llamas, usually healthy and strong, grew thin and listless. Water from the communal spring would not flow when she approached it, forcing her to walk miles to find another source.

More troubling still, people began to avoid her not from choice, but from an inexplicable compulsion. When she approached, they would turn away, unable to meet her eyes or hear her voice. It was as if an invisible barrier had formed around her, cutting her off from all human connection. Children who had once played near her home now gave it a wide berth, sensing something wrong without understanding why.

Kusisita found herself trapped in an isolation more complete than any mourning period could have imposed. She had refused to separate herself from joy for one year, and now she was separated from everything from community, from the land itself, from all the connections that make life meaningful.

In her loneliness, she finally understood what the elders had tried to teach her. The mourning rituals were not punishment or empty tradition. They were the sacred threads that bound person to person, living to dead, human to spirit, individual to community. By refusing to mourn properly, she had not honored her own truth, she had severed herself from truth itself, from the great web of reciprocity and relationship that sustained all life in the Andes.

But her realization came too late.

One morning, the villagers found that Kusisita’s home stood empty. They searched the hills and valleys, calling her name, but she did not answer. Finally, an old shepherd discovered what had become of her. On a remote hillside, far from any path, stood a stone that had not been there before, a huaca, a sacred stone outcropping in the shape of a woman. Her face was forever turned away from the village, her arms wrapped around herself in eternal isolation.

The apus had transformed her into stone, a permanent reminder of the cost of breaking sacred bonds. She had refused to honor the dead and respect communal rituals, choosing individual will over collective wisdom. Now she stood forever outside the community she had rejected, neither living nor dead, but caught between worlds, a monument to emotional imbalance and social rupture.

To this day, travelers who pass that lonely stone sometimes hear the wind whistling through its crevices, a sound like distant weeping. The villagers say it is Kusisita, finally mourning all that she lost when she refused to mourn what custom demanded. They leave offerings at the huaca not to honor her, but to remember the lesson she embodies that we are not isolated beings who can define our own truths in defiance of sacred obligations, but part of a greater whole, bound by rituals that honor both the living and the dead, the individual and the community.

Click to read all Andean Highland Folktales — echoing from the mountain peaks of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.

The Moral Lesson

This powerful Quechua tale teaches that individual must sometimes bow to communal wisdom and sacred obligation. Kusisita’s story reminds us that rituals and traditions are not arbitrary restrictions but vital threads that weave individuals into the fabric of community and maintain balance between the human and spiritual worlds. Her transformation into stone illustrates the Andean concept of reciprocity ayni and shows that refusing to participate in the give-and-take of social and spiritual obligations leads to isolation and loss of one’s very humanity. The legend emphasizes that true freedom comes not from rejecting all constraints, but from understanding and honoring the sacred bonds that connect us to others, to our ancestors, and to the land itself.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Kusisita in this Peruvian Quechua legend? Kusisita was a woman from a highland Andean village whose name meant “joyful.” She was known for her bright spirit and refusal to let sorrow affect her. After her husband’s death, she became infamous for refusing to follow the sacred mourning rituals required by Quechua tradition, leading to her tragic transformation and isolation.

Q2: Why were mourning rituals so important in Quechua culture? In Quechua tradition, mourning rituals were sacred obligations that maintained harmony between the living and the dead, humans and spirits. They were communal practices that honored the deceased, helped guide souls to the afterlife, and reinforced social bonds. These rituals represented the Andean principle of ayni (reciprocity) and were essential threads holding the community together spiritually and socially.

Q3: What were the specific mourning requirements Kusisita refused to follow? Kusisita was expected to wear black clothing for one full year, refrain from singing and dancing, avoid wearing jewelry or bright colors, participate in monthly offerings at her husband’s burial site, and demonstrate her grief publicly through weeping. She refused all these obligations, choosing instead to wear colorful clothing, sing, and continue living joyfully.

Q4: How did the spirits punish Kusisita for refusing mourning rituals? The spirits, particularly the apus (mountain spirits), gradually isolated Kusisita from everything that sustained life. Her crops withered while neighbors’ thrived, her llamas grew sick, water would not flow for her, and people became unable to see or hear her. Finally, she was transformed into a stone huaca forever separated from the community and trapped between the worlds of living and dead.

Q5: What is a huaca in Andean culture and tradition? A huaca is a sacred stone, place, or object in Andean cosmology that holds spiritual power and significance. Huacas can be natural formations or transformed beings that serve as connections between the physical and spiritual worlds. In this legend, Kusisita became a huaca as punishment a permanent stone monument representing the consequences of breaking sacred social and spiritual bonds.

Q6: What does this legend teach about individual freedom versus community obligation? The legend teaches that in Andean worldview, individuals exist within a web of reciprocal relationships and sacred obligations. While Kusisita believed she was honoring her own truth by refusing mourning rituals, she actually severed herself from the communal bonds that give life meaning. The story emphasizes that true belonging requires participating in collective practices, even when they conflict with personal desires.

Source: Adapted from the Huarochirí Manuscript (Chapter 12) and Quechua ritual law narratives

Cultural Origin: Quechua Indigenous Peoples, Huarochirí Province, Peruvian Andes