Long ago, in a village perched high on the terraced slopes of the Peruvian Andes, where the air was thin and crisp and the mountains scraped the belly of the sky, there lived a group of children who knew no fear. They were shepherd children, responsible for watching over their families’ llamas and alpacas as the animals grazed on the tough mountain grasses. Day after day, they roamed the high pastures together, their laughter echoing across the valleys, their games filling the long hours between dawn and dusk.

These children had grown up surrounded by the majesty and power of the mountains. They knew the rumble of avalanches, the bite of icy winds, and the sudden fury of mountain storms. But familiarity had bred in them not respect, but a dangerous carelessness. They had forgotten or perhaps never truly learned that the forces of nature were not mere phenomena but living powers, spirits with consciousness and will, deities who demanded reverence and proper conduct from all who dwelled in their domain.

Click to read all South American Folktales — timeless stories from the Andes to the Amazon.

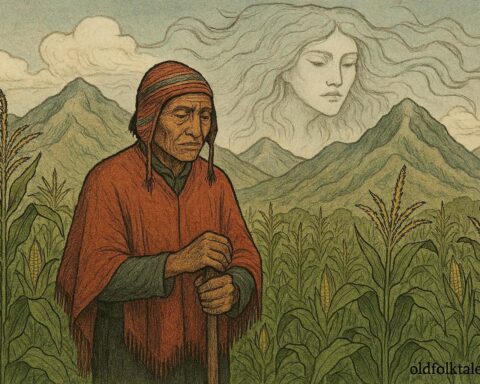

Among these forces, none was more powerful or more temperamental than Illapa, the great thunder deity who ruled the storms. Illapa was both provider and destroyer, the one who brought the lightning that split the sky and the rain that fed the crops. The farmers prayed to him during planting season, offering him chicha and coca leaves, begging him to send gentle rains rather than destructive hail. They taught their children to lower their eyes when lightning flashed, to speak softly when thunder rolled, to recognize the presence of the divine in the violence of the storm.

But these particular children had grown bold and thoughtless. They mocked what they should have honored.

One afternoon, as they tended their animals on a high plateau, dark clouds began to gather over the peaks. The wind picked up, carrying with it the electric scent that always preceded a mountain storm. Most children would have immediately begun herding their animals to shelter, but these children saw an opportunity for entertainment.

As the first lightning bolt split the darkening sky, illuminating the landscape in harsh white brilliance, the oldest boy laughed and raised his arms to mimic the jagged shape.

“Look!” he called to his companions. “I am Illapa! I throw lightning!”

The other children giggled and joined in the game. They danced and shouted, raising sticks to the sky as if they were casting thunderbolts. When the thunder rumbled across the mountains, shaking the very ground beneath their feet, they stomped and roared, mocking the deity’s voice with their childish imitations.

“Boom! Crash! I am the mighty thunder!” they shouted, doubling over with laughter at their own audacity.

One girl, smaller than the rest, picked up a flat stone and threw it toward the clouds. “Illapa cannot catch me!” she taunted. “Illapa is just noise and light!”

The storm was building now, the clouds roiling and churning directly overhead, turning day into premature twilight. The llamas and alpacas grew nervous, clustering together and making soft, anxious sounds. But the children paid no attention. They were too absorbed in their irreverent game, their mockery of the sacred power that controlled their lives and livelihoods.

Lightning flashed again, closer now, and the thunder that followed was so loud and immediate that it felt like the sky itself was cracking open. But instead of frightening the children into silence and respect, it only encouraged them to greater boldness.

“Illapa is angry!” the oldest boy shouted gleefully. “But he cannot touch us! We are too clever for the thunder god!”

That was when the sky seemed to split apart.

A massive bolt of lightning struck the ground directly in front of the children, so bright that it burned white spots into their vision, so close that they could smell the sharp, acrid scent of scorched earth. The thunder that accompanied it was not a sound but a physical force that knocked them all to the ground, stunning them into sudden, terrified silence.

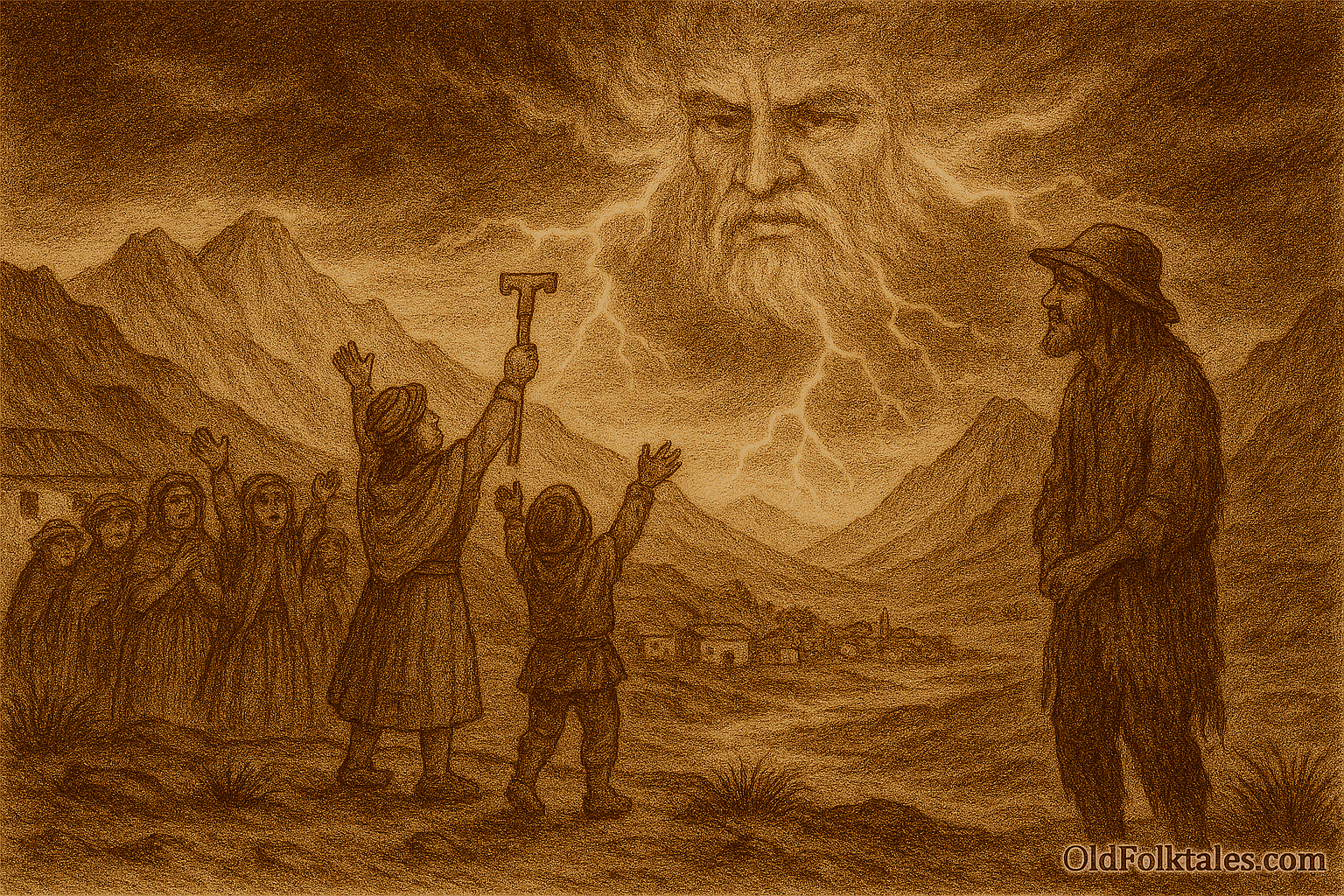

As they lay there, hearts pounding, ears ringing, the sky above them began to change. The churning clouds took on a form, a vast and terrible face made of storm and shadow. It was Illapa himself, revealing his presence, letting these foolish children see the true nature of the power they had so carelessly mocked.

His voice, when it came, was thunder itself not an imitation but the real, primal force of storm speaking words:

“You dare to mock me? You dare to treat the power of storm as a plaything? I who bring the rain that feeds your families’ fields! I who hold life and death in every flash of lightning! You have shown disrespect not only to me but to the sacred order of all things!”

The children were paralyzed with terror, finally understanding the magnitude of their transgression. They tried to cry out for forgiveness, but their voices were lost in the roar of wind and thunder that Illapa commanded.

“You wished to play with thunder?” Illapa’s voice rolled across the mountains. “Then you shall be bound to it forever!”

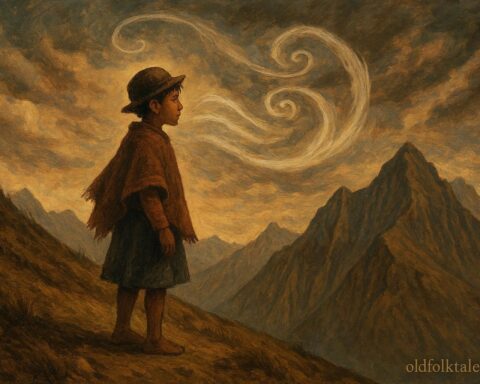

Lightning struck again, engulfing each child in blazing white fire. But this was not the lightning that kills it was the lightning that transforms. The children felt themselves being pulled upward, their bodies becoming weightless, their very substance changing. They were being torn from the earth, lifted higher and higher into the darkening sky.

The villagers, who had been watching the storm from the safety of their homes, saw a strange sight: brilliant points of light rising from the high plateau where the shepherd children had been tending their flocks. The lights spiraled upward through the storm clouds, spinning and swirling until they broke through into the clear space above the tempest.

When the storm finally passed and the night sky cleared, the villagers looked up to see something new in the heavens. There, arranged in a distinctive pattern that had not been there before, shone a small cluster of stars. They flickered and pulsed as if with some inner turmoil, and their arrangement seemed almost to suggest the forms of children frozen in the act of play.

The village elders recognized this as Illapa’s judgment. The children had been transformed into stars not killed, but removed from the earthly realm and placed in the sky as eternal reminders of the importance of respect for sacred forces.

But Illapa, though fierce in his punishment, was not without mercy or purpose. Over time, the people came to understand that these stars served a vital function. They appeared at specific times of the year, rising in the night sky to signal important moments in the agricultural calendar. When these stars reached certain positions, the farmers knew it was time to plant their crops. When they appeared in a different configuration, it was time to prepare for harvest.

The children, in their transformation, had become useful despite their transgression. They had been made into guides for the very farming communities they had endangered with their disrespect. Illapa had turned their punishment into service, demonstrating that even divine anger could be tempered with wisdom and ultimate purpose.

The older people taught the younger ones to look for these stars, to read their positions and movements. They told the story of the irreverent children, ensuring that each new generation understood the dual lesson: first, that nature’s forces demand respect and proper reverence; and second, that Illapa, though stern in justice, could transform even punishment into something that served the community’s needs.

On stormy nights, when lightning flashed and thunder rolled across the Andean peaks, parents would point to those stars and remind their children: “See there? Those were once children like you, who forgot that the powers of nature are sacred. They learned their lesson too late, but through their transformation, they serve us still. Let their story teach you what they learned through suffering that reverence for the divine forces of storm and sky is not optional, but essential.”

And so the stars shine on, visible to Quechua farmers who still look to the heavens for guidance in planting and harvesting. The children dance eternally in the night sky, no longer mocking the thunder but serving it, their transformation a permanent reminder that the sacred forces of nature are not to be trifled with, and that even divine punishment can carry within it the seeds of redemption and service.

Click to read all Andean Highland Folktales — echoing from the mountain peaks of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.

The Moral Lesson

This Quechua legend teaches the fundamental importance of respecting the sacred forces of nature, particularly the powerful weather deities who control the rain and storms vital to agricultural survival. The children’s story demonstrates that what seems like mere natural phenomena thunder, lightning, storms are actually manifestations of conscious divine powers that demand reverence and proper conduct. Their transformation into stars illustrates the Andean concept that even transgression and punishment can be transformed into something useful for the community, as the children became agricultural guides in the night sky. The tale emphasizes that familiarity with nature’s power should breed respect rather than carelessness, and that mockery of sacred forces brings severe consequences while also showing that redemption and purpose can emerge even from punishment.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Illapa in Quechua mythology and Andean culture? Illapa is the thunder and lightning deity in Quechua cosmology, one of the most important and powerful gods in Andean religion. He controls storms, rain, lightning, and weather patterns essential to agriculture. Farmers prayed to Illapa for gentle rains and protection from destructive hail, making offerings of chicha and coca leaves. He represents both the life-giving and destructive aspects of natural forces.

Q2: What transgression did the children commit in this Andean legend? The children committed the serious offense of mocking Illapa during a thunderstorm. They imitated his lightning and thunder, taunted him verbally, and treated his sacred power as entertainment rather than showing proper reverence. Their disrespect demonstrated dangerous carelessness toward forces that demanded honor and fear, violating the fundamental Andean principle of reciprocal respect between humans and nature spirits.

Q3: How did Illapa punish the disrespectful shepherd children? Illapa struck the children with transformative lightning that lifted them from the earth and carried them into the sky, where they were transformed into stars. This punishment removed them from their earthly lives and families, binding them eternally to the heavens as a permanent reminder of the consequences of disrespecting sacred natural forces.

Q4: What purpose do the children-stars serve in Quechua agricultural tradition? After their transformation, the children became a useful constellation that serves as an agricultural calendar for Quechua farmers. Their positions and movements in the night sky signal important farming times when to plant crops, when to prepare for harvest, and other crucial moments in the agricultural cycle. Their punishment was thus transformed into community service.

Q5: What does this legend teach about the relationship between humans and nature in Andean culture? The legend emphasizes the Andean worldview that natural forces are conscious, powerful deities requiring constant respect and proper ritual attention. It teaches that familiarity with nature should never lead to carelessness or disrespect, and that the forces providing for human survival particularly weather and storms must be approached with reverence, humility, and appropriate ceremonial behavior.

Q6: How does this story reflect Quechua astronomical and farming knowledge? The story demonstrates the deep integration of astronomy into Quechua agricultural practice. Andean farmers relied on stellar observations to time their planting and harvesting, and constellations served as celestial calendars. This legend provides both a cautionary tale and an explanation for specific star patterns used in agricultural timing, showing how mythology encoded practical astronomical knowledge within moral instruction.

Source: Adapted from Quechua oral astronomy traditions and Andean cosmology studies referencing Huarochirí material

Cultural Origin: Quechua Indigenous Peoples, Peruvian Andes and Highland Agricultural Regions