The mountain paths of the Andes are ancient beyond memory, worn smooth by countless feet over countless generations. They wind through high passes where the air grows thin and precious, descend into valleys where mist clings to terraced fields, and traverse lonely stretches where a traveler might walk for hours without seeing another human soul. It was on such a lonely stretch that a particular traveler found himself one autumn afternoon, when the sun hung low and cold in the western sky.

This traveler was a merchant of sorts, a man who moved between villages trading goods and information. He carried a pack heavy with items acquired through shrewd bargaining, and his mind was equally burdened with thoughts of profit and advantage. He was not a cruel man by nature, but he had learned to see the world primarily in terms of what could benefit him. Respect, gratitude, tradition, these concepts held little value compared to the tangible weight of goods and silver.

Click to read all South American Folktales — timeless stories from the Andes to the Amazon.

As he walked, his thoughts occupied entirely with calculations of what he might gain in the next village, he nearly stumbled over something lying beside the trail. Looking down with irritation at what had almost tripped him, he saw a human skull, weathered and ancient, resting among the stones and sparse grass.

The traveler felt a moment of unease, as anyone might when confronted unexpectedly with evidence of mortality. But the feeling passed quickly, replaced by his habitual pragmatism. The skull was simply an object, a piece of bone left behind when someone had died on this remote trail. It held no meaning, no value, certainly no claim on his attention or respect.

With casual disregard, he kicked the skull aside to clear his path, his foot connecting with the bone with a hollow sound that echoed slightly in the mountain silence.

And then the skull spoke.

“Why do you treat me with such disrespect?” The voice was not loud, but it carried clearly in the thin air, as dry and brittle as ancient parchment, yet unmistakably real.

The traveler froze, his heart suddenly hammering in his chest. He stared at the skull, which had rolled a few feet from where he had kicked it. Surely he had imagined the voice. The altitude sometimes affected travelers’ minds, caused them to hear things that were not there. He shook his head, trying to clear his thoughts, and continued walking, but faster now, eager to put distance between himself and the disturbing object.

“I asked you a question,” the voice came again, from behind him now. “Why do you disrespect the dead?”

The traveler whirled around and saw, to his absolute horror, that the skull was following him. It rolled along the rocky trail, propelled by no visible force, keeping pace with his movements. The empty eye sockets seemed to fix on him with an intelligence that living eyes should not possess, let alone the hollow cavities of a long dead skull.

Terror gripped the traveler. He turned and ran, his pack bouncing heavily on his back, his breath coming in ragged gasps in the thin mountain air. But no matter how fast he ran, the skull kept pace, rolling inexorably behind him, never falling back, never gaining, maintaining the exact same distance.

“Why do you run?” the skull asked, its voice somehow reaching him clearly despite the sound of his own labored breathing and pounding feet. “Are you afraid to face what you have done? Do you think you can outrun the consequences of disrespect?”

The traveler’s lungs burned. His legs trembled with exhaustion. Finally, unable to continue, he collapsed beside the trail, gasping for air. The skull rolled to a stop nearby, settling among the stones as if it had always belonged there.

When the traveler could breathe enough to speak, fear loosened his tongue. “What do you want from me? I meant no harm. It was just a skull, just bone. I did not know…”

“Did not know what?” the skull interrupted. “Did not know that I was once a living person? Did not know that the dead deserve respect? Or did you simply not care, because respecting me offered you no advantage?”

The traveler had no answer. The skull’s words struck too close to the truth of his character.

“Let me tell you a story,” the skull continued, “and perhaps you will understand what you have encountered on this lonely trail.”

The traveler, too exhausted and frightened to do anything else, listened.

“I was once a man much like you,” the skull said. “I walked these same mountains, traveled between the villages, concerned myself with my own advancement and prosperity. I was proud. I thought myself clever and self sufficient. I ignored the old ways, dismissed the traditions as superstition. When others made offerings to Pachamama, I laughed at their foolishness. When the community gathered for festivals and ceremonies, I considered it a waste of time. When elders spoke of respecting the ancestors and honoring the spirits of the land, I turned away, impatient with what I saw as childish beliefs.”

The skull paused, and in that silence the traveler felt the weight of recognition. This was indeed a story about someone much like himself.

“I convinced myself that I owed nothing to the community that raised me, nothing to the earth that fed me, nothing to the ancestors who cleared these very paths I walked. I took what I needed and gave back nothing. I showed gratitude to no one. I respected only my own ambition and my own desires.”

Another pause, longer this time. The wind picked up slightly, carrying the cold of the approaching evening.

“Then I died,” the skull said simply. “Not dramatically. I did not fall from a cliff or freeze in a storm. I simply died, as all people do, my time arrived and my body failed. But here is what I learned too late: the spirits do not forget. Pachamama does not forget. The community of the living may forgive those who wrong them, but the world itself keeps account.”

The traveler found his voice, though it came out as barely more than a whisper. “What happened to you?”

“I died without having lived properly,” the skull replied. “I died without having honored what deserved honor, without having shown gratitude for what I received, without having contributed to the web of reciprocity that sustains both the living and the dead. And so I remain, caught between worlds, neither fully departed nor able to rest. I am bound to this place, to bear witness to others who walk the path I walked, to speak when I am given the opportunity.”

“The opportunity?” the traveler asked.

“When someone shows the same disrespect I showed in life, when someone kicks aside a skull as if it were merely trash, as if the person it once housed had no value, then I am permitted to speak. I am allowed to follow, to question, to reveal what pride and greed and lack of gratitude truly cost.”

The traveler felt his earlier fear transforming into something deeper and more complex. Shame, recognition, and the beginning of understanding.

“What do you ask of me?” he said.

“I ask what you would not have given freely,” the skull answered. “I ask for respect. I ask that you acknowledge that even this bone, stripped of flesh and life, was once part of a person who walked and breathed and mattered. I ask that you recognize your place in the great web of existence, that you are not separate from the land, the ancestors, the community, or the sacred forces that sustain all life. I ask for humility.”

The traveler bowed his head. In that moment, something shifted in his understanding. He saw his life differently, saw the callous calculation and casual disrespect that had characterized his interactions with the world. He saw how he had taken without giving, received without expressing gratitude, walked through sacred spaces and treated them as merely convenient routes to profit.

“I am sorry,” he said, and meant it with a depth that surprised him. “I am sorry for kicking you. I am sorry for treating you as worthless. I am sorry for living as if only my own desires mattered.”

The skull was silent for a long moment. Then it spoke again, and the voice seemed slightly softer, though still carrying the dry rasp of ancient bone.

“Your apology is a beginning,” it said. “But words alone change nothing. Will you return to your village different than you left it? Will you honor Pachamama? Will you participate in the reciprocity that sustains community? Will you show respect to the ancestors and gratitude for what you receive?”

“I will,” the traveler promised. “I will try. I cannot undo my past, but I can change my path forward.”

“Then go,” the skull said. “Return to your village. Live differently. And remember, traveler, that the spirits remain active in this world. The dead are not gone, merely transformed. What we do in life echoes beyond our years, and the choices we make ripple through the web of existence in ways we cannot always see.”

The traveler stood on shaking legs. He looked at the skull one last time, then carefully, reverently, he picked it up. He carried it to a sheltered spot off the trail, a small hollow among the rocks, and placed it there gently. He gathered stones and arranged them around it, creating a simple shrine. From his pack, he took a portion of his food, some coca leaves he carried for trading, and placed these as offerings.

“May you find peace,” he whispered.

When he looked up, the presence he had felt, the sense of the skull’s awareness and voice, had faded. It was simply bone again, resting in its stone shelter. But the traveler knew he had encountered something real, something that had changed him fundamentally.

He continued to his village, and those who knew him noticed the difference immediately. He participated in ceremonies he had previously avoided. He made offerings to Pachamama with sincerity. He showed respect to the elders and gratitude to the community. He never spoke of what had happened on the mountain trail, but he carried the lesson with him every day of his remaining life, a reminder that in the Andean world, the spirits remain active, the ancestors watch, and respect and gratitude are not optional courtesies but essential threads in the web that binds all existence together.

Click to read all Andean Highland Folktales — echoing from the mountain peaks of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.

The Moral Lesson

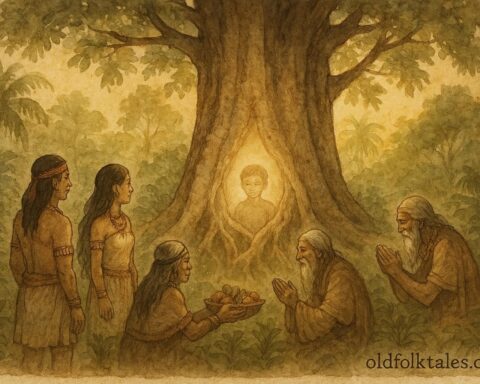

The story of Uma Rimay (The Talking Skull) teaches profound lessons about respect, humility, and the consequences of living disconnected from community and tradition. The traveler’s casual disrespect toward the skull mirrors his broader disregard for Pachamama, ancestors, and the principle of reciprocity that sustains Andean society. The skull, representing the active presence of ancestral spirits, serves as both judge and teacher, confronting the traveler with the truth about his character and the path he has chosen. The story emphasizes that in Quechua cosmology, death does not end a person’s existence or relevance, spirits remain active participants in the world, and the ancestors continue to witness and respond to the actions of the living.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is the main character in “The Talking Skull” and what was his nature?

A: The main character is a traveling merchant who moved between Andean villages trading goods. He was not cruel by nature but had learned to see the world primarily in terms of personal profit and advantage. He held little value for respect, gratitude, or tradition, focusing instead on what could benefit him materially.

Q2: What happened when the traveler kicked the skull beside the trail?

A: When the traveler kicked the skull aside with casual disregard, it spoke to him, asking why he treated it with such disrespect. The skull then began following the traveler as he tried to flee, rolling along the trail by invisible force and continuing to question him about his disrespect toward the dead.

Q3: What did the skull reveal about its former life?

A: The skull revealed it was once a proud man much like the traveler, someone who ignored community laws, dismissed traditions as superstition, laughed at offerings to Pachamama, and showed no respect for ancestors or the spirits of the land. He lived taking what he needed while giving nothing back and showing gratitude to no one.

Q4: Why does the skull remain between worlds instead of resting peacefully?

A: The skull remains caught between worlds because the person died without having lived properly, without honoring what deserved honor, showing gratitude, or contributing to the web of reciprocity that sustains life and death. He is bound to the place to bear witness and speak to others who show the same disrespect he demonstrated in life.

Q5: How did the traveler’s encounter change him?

A: The encounter fundamentally transformed the traveler. He felt genuine shame and recognition, apologized sincerely, and created a simple shrine for the skull with offerings. Upon returning to his village, he participated in ceremonies he had avoided, made sincere offerings to Pachamama, showed respect to elders, and demonstrated gratitude to the community, carrying the lesson with him for the rest of his life.

Q6: What does this story teach about Quechua beliefs regarding death and ancestors?

A: The story teaches that in Quechua cosmology, death does not end a person’s existence or relevance to the living world. Spirits remain active, ancestors continue to witness the actions of the living, and the dead deserve ongoing respect. It emphasizes that proper burial, remembrance, and honoring of ancestors are essential because spirits can respond to disrespect and the boundary between the living and dead remains permeable and significant.

Source: Adapted from Quechua oral traditions documented in “Cuentos Quechuas” published by Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga, Ayacucho, Peru.

Cultural Origin: Quechua people, Peruvian Andean Highlands