Long before hunger learned to speak in loud voices, the Taíno people lived by the rhythms of rain, soil, and shared labor. Their villages rested between forest and sea, and their days were guided by planting, fishing, and ceremony. Food was not owned by individuals but held by the community, and survival depended on balance rather than abundance.

Then came the long dry season.

At first, the people believed it would pass as others had. The elders watched the sky. The farmers loosened soil that no longer welcomed seed. The rivers grew narrow and slow. Maize withered before ripening, and fruits dropped before sweetness arrived. What had once been a generous land became quiet and uncertain.

Among the people lived a woman named Yara, known not for wealth or authority but for attentiveness. She listened when others argued. She noticed when children ate last. She worked the fields even when harvests failed, pressing her hands into soil as if asking it to remember its former kindness.

Yara had lost her husband to illness during the first year of scarcity. She had no children of her own, yet she fed many. When food was divided, she took less than her share. When tempers rose, she spoke calmly. People said she carried the village inside her chest.

One night, when the moon hung thin and pale, Yara dreamed of the zemís, the ancestral spirits who watched over land and people. They did not speak with voices but with images. She saw earth opening gently, not in violence but in invitation. She saw roots swelling beneath the soil, white and strong, storing life instead of demanding it. She woke with her heart beating slowly, firmly, like a drum calling for attention.

At dawn, Yara went to the council house. The elders gathered, faces worn by worry. She told them of her dream, choosing each word with care. Some listened. Others turned away. Hunger had made them suspicious of hope.

Yet that night, Yara returned to the fields alone. She knelt where the soil was poorest and pressed her palms into the ground. She spoke aloud, not to command but to offer. She told the earth she would give what it needed if it would remember how to give in return.

The zemís answered without sound.

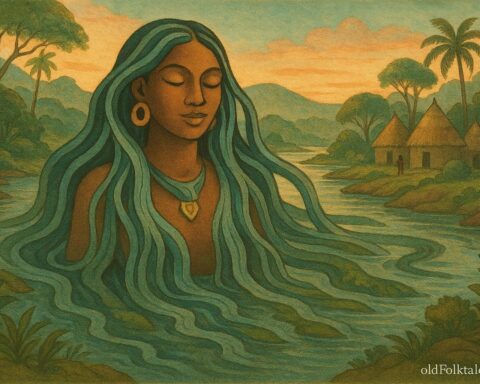

Yara felt a warmth beneath her hands. Not fire, but life moving. She understood then that the dream was not a symbol but a request. The land required a gift equal to its loss. Not grain or water, but flesh and breath. A human life offered freely, not taken by force.

She did not cry. She did not hesitate. Sacrifice, she knew, only held meaning if chosen.

At sunrise, the people found Yara lying still in the field, her body settled into the soil as if it belonged there. No wound marked her. No struggle disturbed the ground. Only her face remained visible, peaceful, her mouth curved as if mid blessing.

The village gathered in grief and fear. Some shouted that the zemís were cruel. Others accused the elders of negligence. But as the sun climbed, the earth around Yara began to change.

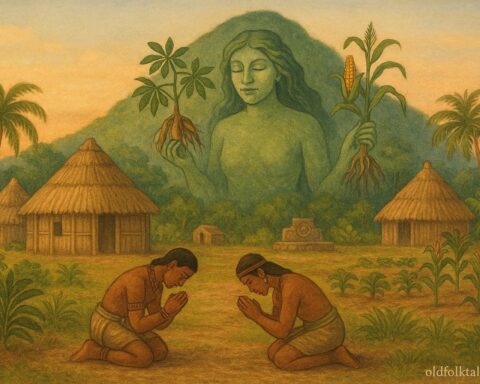

From the place where her body rested, green shoots pushed upward. Leaves unfurled wide and glossy, untouched by drought. Beneath the surface, roots thickened and multiplied, storing nourishment deep in the ground, protected from heat and hunger.

Days passed, and the plants grew strong. The elders dug carefully and uncovered roots unlike any they had seen. When cooked, they were filling. When shared, they did not diminish. The people named the plant cassava and understood that it carried Yara’s gift within it.

They buried her fully then, with ceremony and song. Her name was spoken before every planting. Cassava became the center of Taíno survival, resilient in dry seasons, generous when other crops failed. It was food born of sacrifice, meant to be shared, never hoarded.

The elders taught that cassava must always be planted together, never alone. That it must be prepared with care, because it carried both life and danger if treated without respect. Children were told that cassava grew because someone chose the people over herself.

In time, the famine ended. Rivers widened. Forests healed. But the story of Yara remained. Not as tragedy, but as instruction.

The Taíno learned that survival was not guaranteed by strength alone, but by willingness to give without demand. Cassava reminded them that the earth remembers how it is treated, and that sustenance often comes from acts unseen.

Even generations later, when hands press cassava into bread or root into soil, elders say the land is listening. And somewhere beneath the surface, the First Cassava Woman still feeds her people.

Explore the ancestral legends of Canada, Mesoamerica, and South America’s Indigenous tribes.

Moral lesson

True abundance is born from selflessness and shared responsibility. When survival is treated as a collective duty rather than a personal possession, the earth responds with renewal.

Knowledge check

1 What caused the famine in the Taíno village?

Answer A prolonged dry season and failing crops

2 Who was Yara in the community?

Answer A woman known for care, restraint, and attentiveness

3 What did Yara see in her dream?

Answer Roots growing from the earth as a sign of renewal

4 Why did Yara choose to sacrifice herself?

Answer To restore balance and ensure her people survived

5 What plant grew from the place of her sacrifice?

Answer Cassava

6 What lesson did the people learn from cassava’s origin?

Answer That survival depends on sacrifice, respect, and sharing

Source

Adapted from Taíno agricultural origin stories documented by the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

Cultural origin

Taíno peoples of the Greater Antilles