In a small village perched on the mountainside, where stone houses clustered together against the cold winds and terraced fields descended in green steps toward the valley below, there lived a young man whose intelligence was matched only by his growing skepticism. He had watched the old ways his entire life, the ceremonies performed at planting and harvest, the offerings made to Pachamama, the elaborate rituals that marked every significant moment in the community’s rhythm. While his neighbors participated with reverence, the youth increasingly questioned their necessity.

“Why do we pour chicha on the ground when we could drink it ourselves?” he would mutter, watching the elders libate the corn beer onto the thirsty earth.

“Why burn good coca leaves when they could be chewed?” he complained, as the smoke from offerings spiraled upward toward the mountain spirits, the apus.

Click to read all South American Folktales — timeless stories from the Andes to the Amazon.

His grandmother, whose face bore the lines of eight decades of highland living, would shake her head sadly. “The rituals are not empty gestures, grandson. They are threads that bind our world together, that maintain the balance between giving and receiving. We feed the earth, and the earth feeds us. We honor the spirits, and the spirits protect us. This is ayni sacred reciprocity.”

But the young man, educated in the new ways and influenced by outsiders who dismissed the old beliefs as superstition, grew more stubborn in his dismissal. “Those are just stories for children,” he would reply. “I believe in what I can see, what I can touch. The rest is imagination and wasted effort.”

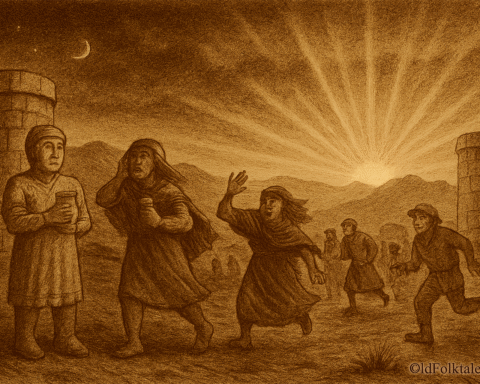

When the time came for the great offering ceremony the ritual performed before planting season to ensure the blessing of Pachamama and the mountain spirits the entire community gathered at dawn. The yatiri, the traditional priest who knew the prayers and proper protocols, had prepared the offering table with meticulous care. Upon the woven cloth lay coca leaves arranged in perfect patterns, llama fat that would burn with sacred smoke, colored threads, sugar figurines, and seeds from every crop the community would plant. Each element held meaning, each placement followed ancient knowledge about how to communicate with the forces that governed rain, sun, and fertility.

The community formed a circle, and the offering bowl began its journey from hand to hand. Each person contributed something, a handful of coca leaves, a blessing whispered over the contents, a prayer for the season ahead. The bowl carried not just physical offerings but the combined intention and faith of the entire village, each person adding their energy to the collective petition for protection and abundance.

When the bowl reached the young man, he looked at it with barely concealed disdain. His neighbors waited, the silence growing heavy with expectation. The yatiri’s ancient eyes watched him steadily, reading the conflict written across the youth’s face.

“This is unnecessary,” the young man said loudly, his voice carrying across the gathered assembly. “I will not waste my time or resources on rituals that accomplish nothing. The success of our crops depends on work and weather, not on burning offerings to spirits that don’t exist.”

He pushed the bowl away without contributing, without offering even a token gesture of participation. A collective gasp rippled through the community. Such refusal was not merely personal, it was a break in the social fabric, a tear in the web of reciprocity that held their world together.

The elders exchanged troubled glances, but the ceremony continued without him. The offerings were burned, the prayers were spoken, and the community returned to their homes with heavy hearts, knowing that the balance had been disrupted.

In the days that followed, illness descended upon the young man’s household like a dark fog settling in the valley. First, his younger sister developed a fever that would not break. Then his mother began suffering from pains that moved through her body like wandering spirits. His father’s prize llama, the strongest in their herd, fell inexplicably lame. The vegetables in their family plot withered even as their neighbors’ plants thrived. It was as if some invisible force had withdrawn its protection from their home, leaving them exposed to misfortune.

The young man, despite his skepticism, could not ignore what was happening. He had studied enough to know these illnesses had physical causes, that the withering crops could be explained by soil conditions, that the llama’s lameness might be a simple injury. Yet the timing, the concentration of troubles in his household alone while the rest of the community flourished, it gnawed at his certainty.

Finally, desperate and frightened, he went to his grandmother. She received him with the gentle sadness of one who has watched the young learn hard lessons for many generations.

“The world is more than what we can see with our eyes, grandson,” she said, her weathered hands holding his. “The rituals are not superstition they are maintenance. When we make offerings, we acknowledge that we are not alone in this world, that we depend on forces greater than ourselves. We express gratitude for what we have received and humility about what we need. The spirits whether you call them that or call them the living forces of nature respond to reciprocity. When we refuse to give, the flow of blessing is interrupted.”

She called the yatiri, who came with his coca leaves and his deep knowledge of how to read the patterns they formed when cast upon a cloth. The old priest performed a divination, and his face grew grave.

“The household is out of balance,” he confirmed. “The refusal to participate broke the web of ayni. The spirits are not punishing they have simply withdrawn. Like a neighbor who is never acknowledged, they turn their attention elsewhere.”

The remedy, the yatiri explained, was not simple apology but sincere participation, a genuine restoration of reciprocity. The young man would need to prepare offerings not out of fear or obligation, but from authentic understanding of the interconnected nature of existence.

And so the young man set about learning what he had dismissed. He gathered coca leaves with prayers, selected the finest llama fat, arranged the offerings with care and intention. When the community next gathered for ceremony, he stepped forward with the offering bowl in his hands, his contribution generous and his heart finally open to the wisdom his ancestors had preserved.

He spoke no grand words, but the sincerity of his participation rang through the morning air like the clear note of a bell. The yatiri nodded with approval, and the community welcomed him back into the circle of reciprocity.

In the days that followed, health returned to his household. His sister’s fever broke, his mother’s pains subsided, the llama regained its strength, and new green shoots appeared in their family plot. The young man could not deny what he had witnessed. He had learned that the world operates on principles deeper than mere material cause and effect, that the rituals his people maintained were not empty gestures but essential practices that honored the web of relationships binding all things together.

From that day forward, he participated in the ceremonies with genuine reverence, understanding finally that community rituals protect not just the physical well-being of the people, but the invisible connections that allow life to flourish in balance between the seen and unseen worlds.

Click to read all Andean Highland Folktales — echoing from the mountain peaks of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.

The Moral Lesson

This Aymara story teaches that community rituals protect both the seen and unseen dimensions of existence through the principle of ayni sacred reciprocity. The young man’s refusal to participate was not simply a personal choice but a disruption of the delicate balance between human community and the natural and spiritual forces that sustain life. Rituals are not empty superstitions but essential practices that maintain relationships, express gratitude, and acknowledge our interdependence with powers greater than ourselves. When we dismiss traditional wisdom and break from collective practices, we don’t just isolate ourselves socially we interrupt the flow of reciprocal blessing that our ancestors understood as fundamental to survival and flourishing.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is the main character in “The Aymara Youth Who Refused the Offering Bowl”?

A: The main character is a young Aymara man from a highland village in Bolivia who was intelligent but increasingly skeptical of traditional rituals and ceremonies. Influenced by outside ideas, he questioned the necessity of offerings and refused to participate in the community’s sacred practices.

Q2: What is ayni and why is it important in Aymara culture?

A: Ayni is the Aymara principle of sacred reciprocity the understanding that life requires balance through mutual giving and receiving between humans, nature, and spiritual forces. It is the foundation of Aymara worldview, expressing the belief that we must give back to the earth, spirits, and community in order to receive blessings and protection in return.

Q3: What happened to the young man’s household after he refused to participate in the offering ceremony?

A: After his refusal, multiple misfortunes struck his household: his sister developed a persistent fever, his mother suffered unexplained pains, his father’s strongest llama became lame, and their family crops withered while neighbors’ plants thrived. The concentrated troubles suggested a disruption in the spiritual balance protecting his home.

Q4: What is the role of the yatiri in Aymara communities?

A: The yatiri is a traditional priest in Aymara culture who possesses deep knowledge of proper ritual protocols, prayers, and spiritual practices. The yatiri prepares offering ceremonies with meticulous care, performs divinations using coca leaves to understand spiritual imbalances, and guides the community in maintaining proper relationships with Pachamama and the mountain spirits (apus).

Q5: What is the cultural origin of “The Aymara Youth Who Refused the Offering Bowl”?

A: This moral tale originates from the Aymara people of the Bolivian highlands, particularly communities living around Lake Titicaca and the Cordillera Real mountain range. It reflects traditional teachings about the importance of ritual participation and the principle of ayni (reciprocity) in maintaining balance between the physical and spiritual worlds.

Q6: How did the young man restore balance to his household?

A: The young man restored balance by genuinely learning about and participating in the offering rituals with sincere understanding rather than skepticism or mere obligation. He gathered offerings with prayers and proper intention, contributed generously when the offering bowl came to him, and rejoined the circle of reciprocity with authentic reverence, which allowed the flow of blessing to resume.

Source: Adapted from Aymara ritual-practice oral traditions recorded in highland folklore collections, including works documented in “The Aymara: Strategies of Adaptation to a Rigorous Environment” edited by Shozo Masuda and “Rituals of Respect: The Secret of Survival in the High Peruvian Andes” by Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff.

Cultural Origin: Aymara People, Andean Highlands, Bolivia (Lake Titicaca region)