Before the islands carried the weight of many histories, the Taíno remembered everything with their voices. Stories were not written. Laws were not carved in stone. Memory lived in breath, gesture, and sound. Elders spoke. Children listened. Songs carried the names of ancestors and the boundaries of rivers.

But time moved, as it always does. Elders passed on. Storms scattered villages. Some words faded. Disagreements grew because people remembered events differently. A promise spoken years before became uncertain. A boundary once agreed upon felt unclear.

The cacique of one large village noticed this first. Disputes took longer to settle. Councils stretched into the night. Younger people argued that old songs were confusing or incomplete. The elders worried. Without shared memory, unity weakened.

Explore the land of La Llorona, trickster coyotes, and magical realism in Mexican folklore

One night, after a council dissolved without agreement, the cacique walked alone to the edge of the village. He lit a small fire and spoke to the zemís. He asked how memory could be protected when voices faltered and time thinned recollection.

As the fire burned low, a deep sound rose from the forest. It was not thunder. It was not wind. It was a steady pulse that matched the heartbeat of the earth.

From the shadows emerged an old man carrying a hollowed log. His hair was white, his skin marked with age, yet his eyes were clear. He set the log near the fire and struck it gently with his hand. The sound was warm and resonant.

Memory must be held, the old man said. Breath alone is too light.

At dawn, villagers gathered as the stranger demonstrated how to shape wood taken respectfully from a fallen tree. He taught them to stretch animal hide across one end and secure it with plant fibers. He showed them how to tune the sound by tightening and loosening the bindings.

This drum, he explained, would carry more than rhythm. It would carry law, lineage, and story. When struck, its voice would guide singers so words would not wander or fade.

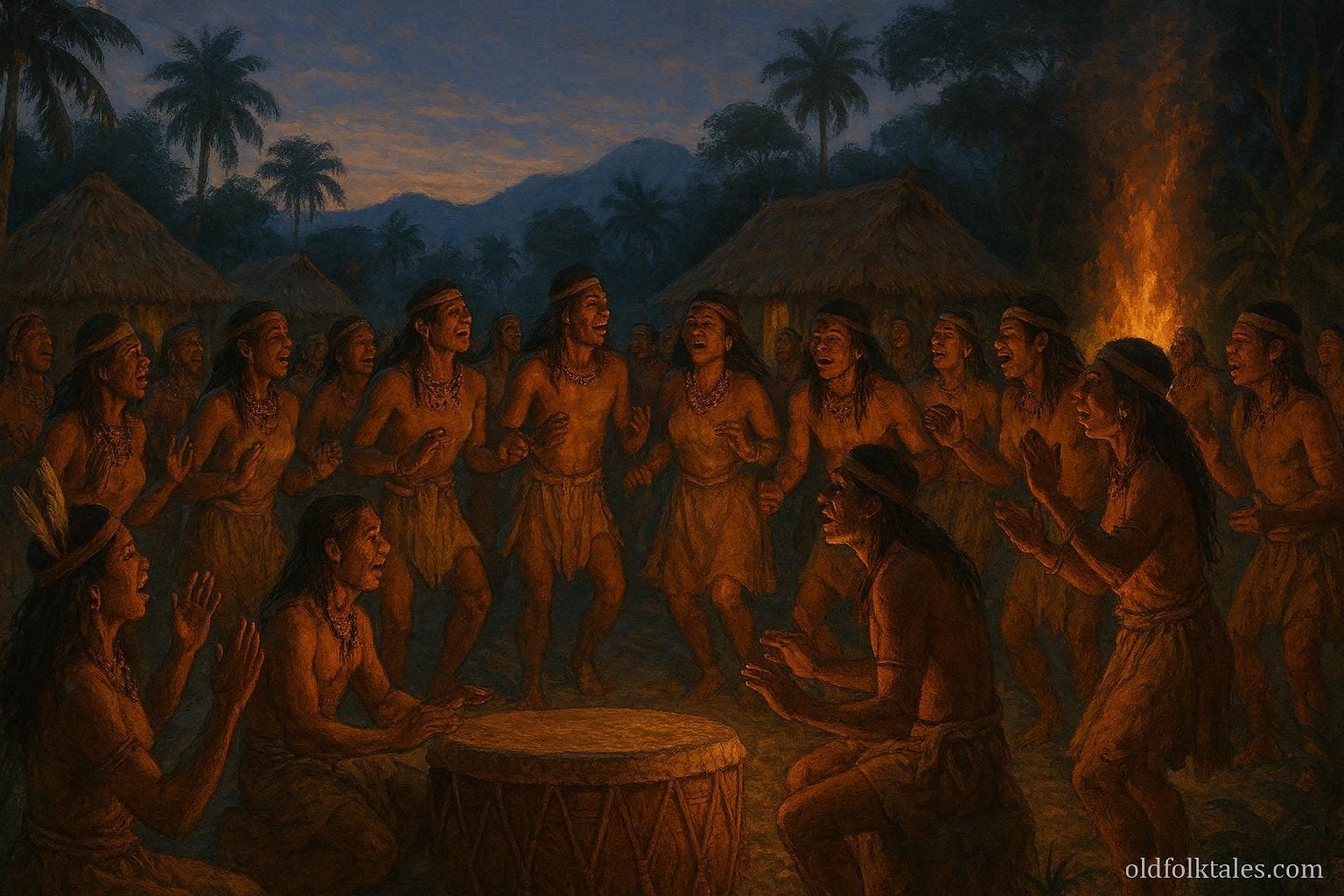

The elders tested it that same day. They sang an old areíto song about the founding of the village. With the drum’s steady pulse, verses aligned. Movements synchronized. Even those who had learned different versions felt the rhythm pull memory into harmony.

Soon, the drum became central to ceremonies. Laws were sung with its beat so they could not be altered easily. Agreements between villages were sealed through shared areíto performances. When a leader died, the drum sounded slowly, guiding songs that named their deeds so none would be forgotten.

But the drum demanded care. It was never struck in anger. It was never played alone. Its voice belonged to the community, not an individual.

A young man once tried to claim the drum’s power. He beat it loudly during a dispute, hoping his voice would dominate others. The sound rang harsh and uneven. The hide slackened. The rhythm faltered. Elders stopped the ceremony.

They explained that the drum did not amplify ego. It strengthened unity. When used wrongly, it withdrew its clarity.

The young man apologized and learned to listen before playing. Over time, he became one of the most respected drummers, known for restraint and sensitivity.

As years passed, other villages requested drums. Knowledge spread, but always with instruction. The drum was never made without ceremony. Songs were never taught without context. Children learned early that rhythm was responsibility.

When storms struck or famine loomed, people gathered and sang history into the present. The drum reminded them of past survival and shared obligation. It kept grief from isolating individuals. It held joy steady so celebration did not forget gratitude.

Long after the first drum’s wood returned to earth, its lesson endured. Even when outside forces threatened Taíno life and culture, rhythm carried memory forward. Songs adapted, but their purpose remained.

The drum did not preserve the past unchanged. It preserved connection. It reminded each generation that unity was not silence but harmony guided by shared pulse.

And so the Taíno remembered who they were, not only through words, but through sound that gathered voices into one body.

Discover ancient tales passed down by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Moral lesson

Memory is strongest when shared. Traditions endure not through dominance or noise, but through collective rhythm, respect, and responsibility.

Knowledge check

1 Why did the Taíno need a new way to preserve memory?

Because spoken memories began to differ and cause disputes.

2 What did the drum represent beyond music?

It carried law, history, and unity.

3 Why was the drum never played alone?

Because its purpose was communal, not individual.

4 What happened when the drum was used in anger?

Its sound lost harmony and the ceremony failed.

5 How did the drum help during difficult times?

It reminded people of shared history and mutual responsibility.

6 What lasting lesson did the Areíto drum teach?

That unity comes from listening and collective balance.

Source

Adapted from Taíno ceremonial practices documented by the Smithsonian Folkways archives.

Cultural origin

Taíno peoples, Greater Antilles.